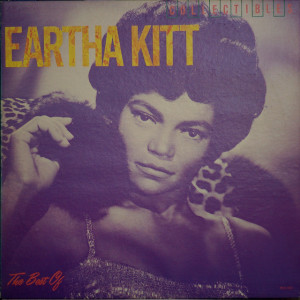

“I am learning all the time. The tombstone will be my diploma.” – Eartha Kitt

“I am learning all the time. The tombstone will be my diploma.” – Eartha Kitt

The late actress and cabaret singer was not the first to see the similarities between life and school. We begin learning at birth and continue throughout our lives. But if our diploma is a stone monument, what happens to the knowledge that we have gained? How do we pass on the insights – the wisdom – that we have acquired on the journey?

One answer to that question is the ethical will, also known as a legacy letter. In its simplest form, this document sums up the most important things an individual has learned. It is usually passed on to children or other family members in the hope that the writer’s experiences and observations will be of benefit to his or her loved ones.

The origin of the ethical will is often attributed to the biblical patriarch Jacob. Lying on his deathbed, Jacob summoned his twelve sons to his side. He commented on the character and behavior of each and then ventured a prediction about the younger man’s future. And he didn’t mince words: Reuben was “unstable as water” and thus unworthy of his inheritance as the firstborn. Dan, a “snake on the road,” would sit in judgment of his siblings. Joseph, ever the favorite son, was “a fruitful bough.”

Common in the Middle Ages among both Jews and Christians, the tradition of writing an ethical will is enjoying something of a renaissance. Two days before his inauguration as the nation’s 44th President, Barack Obama wrote a long letter to his two daughters:

“When I was a young man, I thought life was all about me – about how I’d make my way in the world, become successful and get all of the things I want. But then the two of you came into my world with all your curiosity and mischief and those smiles that never fail to fill my heart and light up my day. And suddenly, all my big plans for myself didn’t seem so important anymore. I soon found that the greatest joy in my life was the joy I saw in yours …

These are the things that I want for you – to grow up in a world with no limits on your dreams and no achievements beyond your reach, and to grow into compassionate, committed women who will help build that world. And I want every child to have the same chances to learn and dream and grow and thrive that you girls have …”

Of course, you don’t have to be a patriarch or a president to write an ethical will. Nor do you need an attorney. You simply need to take the time to reflect on your own unique experiences, to articulate the lessons that life seems determined to teach you and to share those lessons with those you cherish.

Want to know more? Here’s an overview of the Jewish tradition, a look at past-meets-present approaches, a perspective from local Rabbi Elana Zaiman and thoughts from JFS Board President Gail Mautner.

By Don Armstrong

By Don Armstrong

Don is currently the Director of the Aging in Place department and has worked at JFS for the past 16 years. Outside of the office, his interests range from poetry to bonsai, but he always reserves enough time to dote on his two grandchildren.