|

| Sala Nakdimen |

(1920 – 2009)

b. Rzeszow, Poland |

| Wartime Location: Hiding in multiple locations in Poland and Russia |

| “We heard that some people were smuggled, had found a place where the water was not deep across the river, and if people wanted to go to Russia, they were smuggled. We arranged with the Polish officers that we would go. We met the next day. We started to go. I pulled my skirt up, put my things that I had together, and the Germans screamed, ‘Stop!’ Of course we didn’t stop but it was the longest 10 minutes of my life. I expected a bullet in my back any second. They kept screaming, ‘Stop!’ but we kept going and crossed the river. Imagine! Then the Russians screamed, ‘Stop!’ We panicked and just ran. We ran and ran and ran until we hit a little forest, and it was quiet. It took us a little while to realize that no one was following us. We went to the address of some Communists. Such nice fellows.” |

|

|

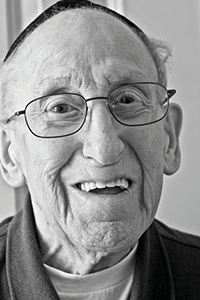

| Fred Roer |

(1920 – 2010)

b. Kerpen, Germany |

| Wartime Location: Germany; Lhodz ghetto, Poland; work/concentration camps in Posen, Poland; Auschwitz concentration camp, Poland |

| “How did I survive? The will to live I guess, being lucky at the same time, able to get some extra food, being able to trade my clothing for food, a Polish worker would share some of his sandwich with me, you know, so I got some extra food. Everyone who survived was just plain lucky and was just at the right place at the right time. Anyone who tells you that they survived because they were smarter — it wasn’t so.” |

|

|

| Eleanor Rolfe |

(1930 – )

b. Hamburg, Germany |

| Wartime Location: Hamburg, Germany; London, England; Amsterdam, Holland; Seattle, WA |

| “I knew my father was in prison. All of our servants had to leave. I remember how they cried when they had to leave. They couldn’t work for us anymore. I could, at that time, feel that my life was falling apart, but my mother tried to shield me as much as she could. And the worst thing was the night the Nazis came into our home and we didn’t know where my father was. He just didn’t come home. That night my mother told me that conditions were very, very dangerous. She was kind of hysterical. She didn’t know what to do, and we sat and cried. Gentiles would take a risk and come and visit. It was right after the Kristallnacht and everybody was watched. I remember the broken windows. It didn’t really sink in, but I was told I had to leave, ‘You’re going to be where your brother is.’ So that softened it, but it turned out not to be the case. I think when life is in turmoil you don’t think about it that much, you just go with the flow. One minute I lived in all the comforts of life, and the next minute, I was all alone. The kids on the kindertransport were all confused and wondering what happened. We weren’t really empathetic to each other. A lot of them cried, and I think that’s why when we got to Holland, the Dutch people heard what was going on and reached into the train and gave us goodies. We really don’t know why the Germans allowed the kindertransport. No one has ever figured that out. But the British people, mainly the Quakers, tried to save as many German children as they could. They couldn’t get adults out, but they could get children.” |

|