Thanks to Real Change for allowing this re-print.

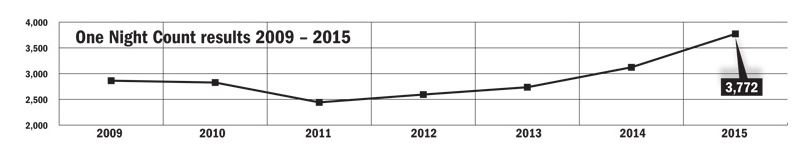

This year’s One Night Count, the 35th, sets a sobering record: 3,772 people outside without any shelter.

A small team of volunteers sank their boots deep into marshy trails and slipped on slick and steep paths through an undeveloped greenbelt in Kent early in the morning looking for anyone who might be sleeping there overnight.

After an hour of walking, they found someone at the end of a trail that was lined with salvaged material to make the muddy walkway easier to traverse: Old car mats, quilts, sheets of fabric and even a pair of jeans were pressed into the mud.

Then, tucked away behind the brush was a small structure built out of tarps and an umbrella.

“They go to some pretty big lengths to get themselves some peace and quiet,” said John Vankat, a case manager at Catholic Community Services in Kent and a volunteer counter for the annual One Night Count.

The volunteers were among hundreds who headed out from 10 command centers around the county to tally the number of people sleeping outside in a count led by the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness’ (SKCCH) on Jan. 23.

As Mayor Ed Murray predicted prior to the count, volunteers found a record number of people.

The volunteers counted 3,772 people sleeping outdoors across King County, the largest number ever in the count’s 35-year history.

The total was 21 percent higher than 2014.

In Seattle, volunteers found 2,813 people, a 22 percent increase over the 2014 figure.

In Kent, where Vankat’s team was counting, volunteers found 135 people, more than double the number found in 2014.

Alison Eisinger, director of SKCCH, said she was in tears when she saw the final figure, a huge increase over the previous year.

“It is not normal to have 3,772 people sleeping outside in the middle of winter,” Eisinger said. “It is not normal, it is not acceptable and it doesn’t have to be that way.”

She said city, county, state and federal governments will have to respond to the crisis in equal measure, noting that 10 consecutive years of cuts to community health and human services funding have added to the problem. It will take additional revenue to respond to the unmet need, she said.

Homelessness has visibly grown in Seattle, with people sleeping in doorways and tents lining freeway greenbelts and downtown parks. But even with this record-high figure, advocates say the population of homeless people is likely larger.

A thousand volunteers cannot count every person sleeping outdoors in the county.

The figure provides a point-in-time illustration of the level of homelessness in the area.

It also provides volunteers with an image of what homeless people face outdoors every night.

After the count in Kent had ended around 5 a.m., the more than 60 volunteers regrouped at a Catholic Community Services office on West Smith Street. There, volunteers reported seeing more people than in past years.

Mary’s Place Executive Director Marty Hartman went to the Kent headquarters this year and was struck by the ages of the people she saw on the streets.

While walking around Kent, her team witnessed a senior man and a teenager.

“The whole wide range of ages was pretty phenomenal to us,” Hartman said.

Volunteers on Vankat’s team found about six people in built structures or sleeping in cars, and they saw other abandoned structures and spaces where more people had slept recently.

The team witnessed a unique picture of homelessness in King County.

Unlike urban areas, where people hunker down in doorways and under bridges and overpasses, Kent’s rural homeless population have become entrenched in their spaces. Even in the dark and from a distance — volunteer counters take precautions to not disturb people who may be sleeping — one can see the care people have put into their homes. Walking up one trail, Vankat spotted deep footprints in the mud.

A few yards later, he passed a bicycle that was clean and looked abandoned. A little while later, he pointed to a flattened patch of grass that looked as though it had been cleared for a campsite.

“The area is definitely lived in,” John said. “There just isn’t anybody here tonight.”

Vankat led the group to a small structure that he had scouted out days before the count.

Built into the side of a retaining wall, it was no larger than a coat closet. Someone had laid chunks of drywall on the floor of the structure since Vankat had seen it earlier in the week.

Clothes and a child’s seat for a bike sat abandoned nearby. But that evening, the space was home to only a few small mice that scattered about the structure.

“This long-term, permanent homelessness is a new perspective for me,” said Heather Post, a member of Vankat’s team and a Catholic Community Services housing specialist. “Next time you’re driving down the street and see a greenbelt or wooded area, you think, ‘What could be in there?’”

Vankat spotted an electric light beaming from one structure he was aware of before the count began. It was a self-made structure hidden behind a fence, which was bolstered with sticks and branches of foliage to provide a visual barrier.

“Someone really cares for these structures day in and day out,” Vankat said. “There’s some permanence to that that you don’t get in the urban settings.”

This article, image and graph are reposted courtesy of Real Change.

By Aaron Burkhalter

Aaron Burkhalter is a Staff Reporter for Real Change.

Feature photo by Jon Williams, Real Change Arts Editor.